Latinx Shakespeares as Performance Methodology

8th August 2023

Professor Carla Della Gatta shares with us her work on Latinx Shakespeares, including how the research towards her recent monograph has helped her to build a wide-ranging open-access archive and resources page at LatinxShakespeares.Org, of interest to BSA members for their researching and teaching.

The growth of Global Shakespeares over the last two decades has expanded the knowledges of theatrical traditions across the world and the cultural, political, linguistic, and economic histories that inform them. My research is an investment in what I have referred to as the diversified local, focusing on a minority population as means to both understand the work of Latinx theatre-makers and to rewrite the history of American Shakespeares so that it includes the over seventy-five years of contributions of Latinx artists and cultures to American Shakespearean performance.

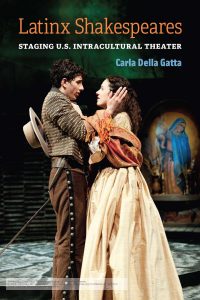

Latinx Shakespeares are Shakespearean productions and adaptations that are made Latinx through dramaturgy, textual adaptation, casting practices, and/or backstage processes. Latinx Shakespeares: Staging US Intracultural Theater (University of Michigan Press, 2023, open-access),draws a theatre history, one with stops and starts and theatrical traditions with surprisingly long arcs. These works range from culturally-appropriative musical theatre with Puerto Rican characters such as West Side Story (Broadway, 1957) to engagements with Cuban religious practices—both Catholic and Indigenous African—such as Hamlet, Prince of Cuba (Asolo Repertory, 2012) to immigration narratives about border crossings between Mexico and the US, such as La Comedia of Errors (Oregon Shakespeare Festival, 2019). The trajectory reveals no direct through line from white artists taking up Latinidad to Latinx artists taking up Shakespeare, but as more Latinx theatre-makers became involved in these productions, the range of dramaturgical practices and nuanced depictions of Latinx expanded.

Latinx Legibility Onstage and Off

There are no Latinx characters or settings in Shakespeare, as the ethnic category of Latino was coming into formation during Shakespeare’s time. According to the US government, there are four races: Black/African American, white/Caucasian, Indigenous/Native American, and Asian. Hispanic/Latino is an official ethnicity—only as of the 1980 Census—and can be of any race.[1] Latinx is the gender non-binary term for Latino, the peoples who live in the United States who are a product of, or descended from, Spanish colonization. These are homogenizing and problematic categories for identity, and my use of them in Latinx Shakespeares (and here in this blog) pushes on those limitations.[2]

One of the challenges in historicizing the role of Latinx peoples is in the recognition of Latinx. For example, in the long-running production of Othello with African American actor Paul Robeson in the titular role, Puerto Rican actor José Ferrer played Iago (Broadway, 1943). None of the reviewers of Ferrer’s performance ascribed the stereotypes or tropes that often get applied to Latinx actors today, that they are ‘fiery,’ ‘hot’, etc., as the ethnic category of Hispanic (later Latino) had not yet fully gained traction. Although audiences knew that Ferrer was Puerto Rican, the combination of his racial whiteness and a lack of a recognized official ethnic category both contributed to a lack of recognition of his identity.

More than seventy-five years later, Latinx Shakespearean productions address such issues of Latinx legibility, including colorism and anti-Blackness within Latinx communities. In Alex Alpharaoh’s 2019 O-Dogg: An Angeleno Take on ‘Othello’, the action is set during the six days of the 1992 LA uprisings that followed the acquittal of white police officers who had beaten a Black man. Alpharaoh rewrites Othello to Afro-Latinx, Iago as Indigenous Latinx, the Emilia character as white-passing Latinx, and the Desdemona character as Korean-American. The adaptation simultaneously maps the historical interracial violence throughout the city of Los Angeles and the intra-ethnic biases that play out within Latinx communities on personal level.

One of the ways that Latinx characters are made legible is often through an emphasis on the aural. Nearly all Latinx Shakespeares include some Spanish to signal Latinidad, whereas with each passing decade, Latinx theatre includes less and less Spanish. Because Latinx are absent from Shakespeare’s canon and visually racially-diverse, theatre-makers embellish the aural through language, accents, music, and the larger soundscape. What I term a Latinx acoustemology for Shakespeare is this aural excess, or auralidad, that is invited through the openness of Shakespeare’s language and invites the nuances of identity that lead to a reformulation of Latinx as an identity category.[3]

Latinx Shakespeares as Methodology

Integral to writing a theatre history, especially one of adaptation, is the ‘both/and’ of creative/critical practice. As a scholar-practitioner, I draw on the knowledge of artists and understand and advocate for creative work as an act of criticism, and throughout Latinx Shakespeares, the output of artists that is theatre-making is on equal plane to the output of academics that is our scholarship. In so doing, this type of performance criticism takes seriously the aesthetics, processes, and creative practices of Latinx art-makers and positions itself against binarism and the divisive ‘us-them’ mentality that looks to art to explicitly engage ‘the political’.

For Shakespeare to be made Latinx, adaptations and concept productions cannot merely integrate thematic issues of the border, Latinx characters, or include Spanish. Latinx Shakespeares at their best are acts of theatrical bilanguaging, a process I describe as ‘a liberation from discrete genres of theatrical storytelling as well as Shakespearean English [that] pushes against the idea of universality to expand theater communities for a specific locality’ (p. 109). The act of theatrical bilanguaging involves an inclusion of backstage processes and performance methods and crosses dramaturgical, ethnic, and linguistic borders.[4] For example, in Chapter Four of Latinx Shakespeares, I attend to three Hamlet adaptations that take different approaches to mixing performance—ritual, ceremonial, and devised theatre practices—and theatrical practices to create space for Latinx subjectivity and interiority. Each of these productions addresses the crisis of the self that results from coloniality by crossing multiple borders, ‘linguistic and cultural, religious and ritualistic, within the play and without’ (p. 27).

Latinx Shakespeares demonstrate how early strategies of division such as the West Side Story effect—the staging of cultural difference of any kind in Shakespeare as cultural-linguistic difference—can be transposed to a bridge through theatrical bilanguaging, an act of ‘listening for commonality rather than difference’ as an ‘act of creating bridges is a look to the future for the new American theater’ (p. 174). They make the case that Shakespeare can be staged as ethnic theatre when created and staged through theatrical bilanguaging.[5]

Writing an Archive

Latinx Shakespeares examines Latinx-themed Shakespearean productions. As my research into Latinx engagement with Shakespeare began to expand backwards historically and forwards to new productions, it also expanded more widely to bilingual and semi-bilingual theatre, the Latinx artists who perform, design, and direct Shakespeare without a Latinx theme, pedagogical practices, translation practices, and Latinx ontologies for theatre-making through stories that must be adapted to embrace our cultures. As a result, I co-edited with Trevor Boffone Shakespeare and Latinidad (Edinburgh University Press, 2021), a collection of essays and interviews with twenty-five contributors that extends the breadth of possibilities of engaging Shakespeare for Latinx cultures.

I wanted to ensure that the history of the myriad intersections of Shakespeare and Latinidad is readily available and accessible to make clear Latinx contributions to American Shakespeares. Along with the open-access monograph that was published in January, I launched the first online archive of Latinx theatrical adaptation in February. LatinxShakespeares.Org goes beyond Latinx Shakespeares and intersections of Shakespeare and Latinidad to adaptations of other (white) canonical literatures including Greek and Roman plays, Spanish Golden Age dramas, and adaptations of Lorca, Chekhov, Ibsen, Molière, and more. With over twenty contributors at the outset, its launch included more than 150 Latinx Shakespeares, more than 30 bilingual and/or Latinx-authored (but not themed) Shakespearean adaptations, and nearly 100 Latinx-themed and/or authored adaptations of other western literatures.

The archive continues to grow, with more than twenty-five productions and adaptations added in the first six months. It is Phase I of a larger project of creating community through archiving theatre history. I have been in touch with over 250 theatre-makers—to gain permission to include their ephemera and photographs and to learn about their work—and I have heard from dozens more, each excited to be part of such a lengthy and creative theatrical legacy. For practitioners, the archive is a resource of contemporary dramaturgies for classical theatre, and for scholars, it is a database of strategies for engaging Shakespeare by and for an ethnic group. I would love to hear from scholars and artists how it is being used in their research, and from those who wish to contribute a performance review, drama analysis, or guest blog. Please contact me at carla[at]umd[dot]edu.

[1] Latinx is a geographical term, based on a shared history and culture, whereas Hispanic is a language-based term for those from Spanish-language dominant countries.

[2] Shakespeare is pluralized as ‘Shakespeares’ to signal an interdisciplinary, Cultural Studies approach. The diversity of perspectives, methodologies, and subject matters is indicated in this pluralization, unlike older disciplines such as English, Literature, and Theatre.

[3] ‘Acoustemology’ is a portmanteau for ‘acoustic epistemology’ and was coined by Steven Feld. See Wes Folkerth, The Sound of Shakespeare, New York: Routledge, 2002. 106.

[4] I adapt for the theatre Walter Mignolo’s concept of languaging that is a ‘way of life between languages: a dialogical, ethic, aesthetic, and political process of social transformation’. Walter Mignolo, Local Histories / Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), p. 265.

[5] I define ethnic theatre as a ‘for us, by us’ with examples such as the Yiddish theatre, Armenian theatre, and early Latinx theatre.